How some people get drunk from their own gut bacteria

On Jan. 8, 2026, researchers reported results from a study on the largest cohort of autobrewery syndrome (ABS) patients to date seems to confirm bacteria as the major culprit. The research, published in Nature Microbiology, could point to new treatments for the syndrome that involve altering alcohol metabolism in patients’ gut microbes.

Since the late 19th century, doctors have reported occasional cases in which patients seemed drunk after a meal despite not consuming a drop of alcohol. Researchers long attributed the rare and vexing condition, known as ABS, to fermentation of carbohydrates by excess fungi in the gut, until a breakthrough 2019 paper linked a few cases to ethanol-producing bacteria.

The study offers enough evidence to retire the fungal hypothesis, says microbiologist Jing Yuan of Beijing’s Capital Institute of Pediatrics, who led the 2019 study but wasn’t involved in the new work. The researchers “showed that the condition is primarily driven by bacterial ethanol fermentation,” she says.

Much of what is known about ABS comes from anecdotes and case reports, many of them describing drunkenness after ingesting carbohydrates: One young woman was unable to walk after receiving glucose during a test for diabetes, for example. Patients can face severe social consequences, such as losing a job over daytime drunkenness. “This disease is terrible on families,” says gastroenterologist and ABS researcher Bernd Schnabl of the University of California San Diego, who led the new study. “Patients are not believed”—even by their doctors—when they insist they aren’t drinking.

As expected, stool from the ABS patients in the study produced alcohol in culture, whereas stool from household controls did not. (Healthy people produce trivial quantities of alcohol in their guts that are easily metabolized, Schnabl notes.) The ABS patients also had higher levels of enzymes indicating signs of liver damage, and one even had scarring of the liver, known as cirrhosis.

When a physician does confirm the syndrome, by administering glucose followed by a breathalyzer or blood alcohol test under strict supervision, treatment typically involves antifungals and antibiotics, along with a low-carbohydrate diet meant to avoid feeding the ethanol-producing microbes. But even with these interventions, patients can struggle for years with flare-ups of symptoms.

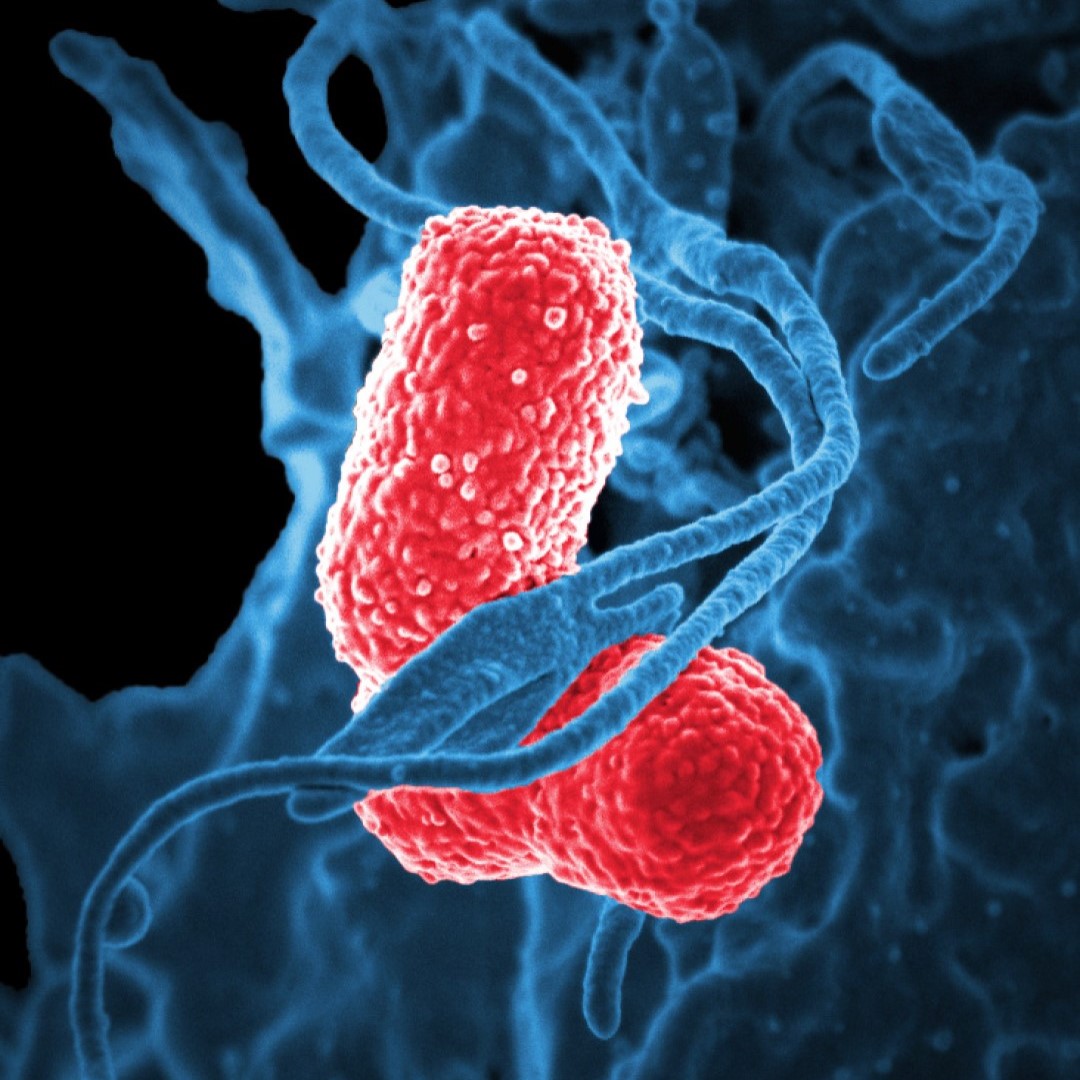

As strong as the new work is, it still leaves big holes in the understanding of ABS, Bajaj says. Even with years of follow-up, the researchers “found no smoking gun” that could account for why patients developed the disease, he notes, with the exception of one who had gut inflammation related to Crohn disease. Because Klebsiella and E. coli aren’t unique to ABS patients, “we are still left with a quandary as to whether the microbiome is the be all, end all,” he says. “We still don’t know why so many people who have these bacteria in them at all times don’t develop the syndrome.”

Tags:

Source: American Association for the Advancement of Science

Credit: Image: Colorized scanning electron micrograph showing carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae interacting with a human neutrophil. Courtesy: National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases.