UCLA team discovers how to target ‘undruggable’ protein that fuels aggressive leukemia

On Dec. 9, 2025, researchers at the UCLA Health Jonsson Comprehensive Cancer Center announced they have identified a small molecule that can inhibit a cancer-driving protein long considered impossible to target with drugs — a discovery that could open the door to a new class of treatments for leukemia and other hard-to-treat cancers.

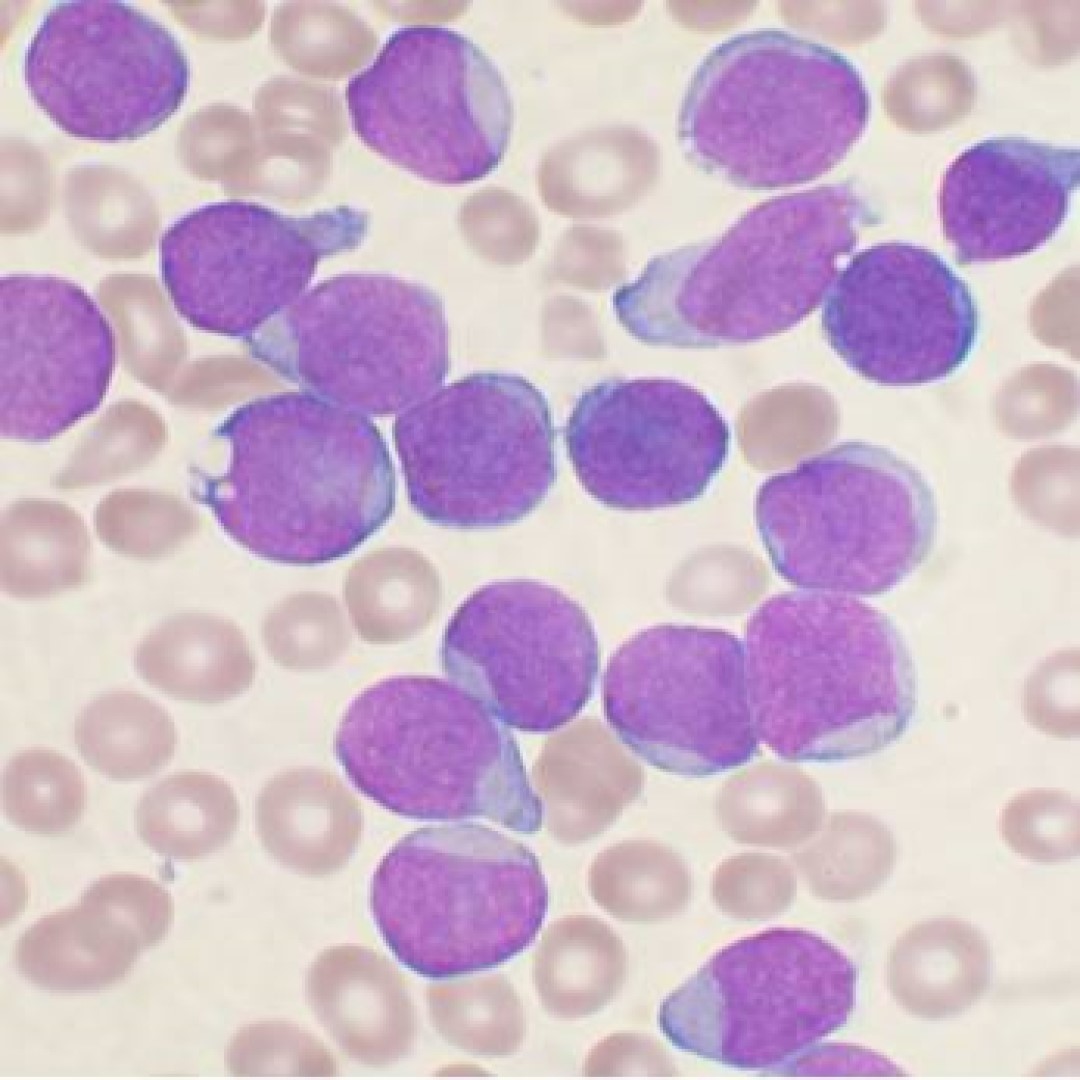

The compound, called I3IN-002, disrupts the ability of a protein known as IGF2BP3 to bind and stabilize cancer-promoting RNAs, a mechanism that fuels aggressive forms of acute leukemia. The study, published in the journal Haematologica, found the molecule not only slowed leukemic cell growth but also triggered cancer cell death and reduced the population of leukemia-initiating cells that sustain the disease.

IGF2BP3 belongs to a family of RNA-binding proteins that are normally active only at the earliest stages of human development. After birth, their activity largely shuts down, but in some cancers, including leukemia, brain tumors, sarcomas, and breast cancers, IGF2BP3 switches back on. But for decades, researchers have been unable to develop a drug to disable it because IGF2BP3 lacks the typical “pockets” or enzymatic features that most drugs latch onto, which has made it notoriously difficult to target.

To find a potential inhibitor, the team used a high-throughput screening system that tested approximately 200,000 compounds from the UCLA Molecular Screening Shared Resource led by Dr. Robert Damoiseaux to find candidates that could block IGF2BP3 from binding to its RNA targets, the core function that enables the protein to drive cancer growth.

After early hit compounds were identified, Rao turned to UCLA chemistry professor Dr. Neil Garg, whose group helped analyze the compounds’ structure, and recognized a pattern that seemed to be preserved. From that search, the second compound identified, I3IN-002, emerged as a lead compound, showing potent activity at low micromolar concentrations and producing effects that closely mirrored what happens when the IGF2BP3 gene is deleted entirely. Garg’s lab then created a method to synthesize it in-house, an essential step for advancing it through additional testing.

Once I3IN-002 was synthesized, the researchers put the molecule through a series of rigorous tests to determine whether it truly acted on IGF2BP3, the cancer-driving protein they aimed to target.

They found that in leukemia cells that rely on IGF2BP3 for growth slowed dramatically when exposed to the molecule, while cells lacking the protein showed only a minimal response, a strong indication that the compound is acting on its intended target. In the treated IGF2BP3-positive cells, the molecule triggered apoptosis, or programmed cell death, and interfered with the protein’s ability to bind RNA, a critical step in its tumor-promoting activity. It also reduced the expression of several cancer-promoting genes normally stabilized by IGF2BP3, further underscoring its potential as a highly specific therapeutic candidate.

These effects were far weaker in cells where IGF2BP3 had been genetically deleted, offering strong evidence that the molecule is working exactly where intended. Additional gene expression, RNA binding, thermal shift and drug-stability assays confirmed that I3IN-002 physically binds to IGF2BP3 and alters its function, one of the clearest demonstrations to date that this long-considered “undruggable” class of RNA-binding proteins can, in fact, be targeted with small molecules.

The team is now working to create next-generation analogs of I3IN-002 that are more potent, more stable and more suitable for testing in animals and eventually humans.

Tags:

Source: University of California, Los Angeles

Credit: